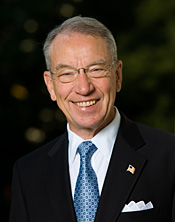

Floor statement of Senator Chuck Grassley on how the Senate should operate, delivered Monday, February 24, 2014:

Mr. President, either tonight or tomorrow, the Senate will consider several district court nominees. These nominees will be brought up, considered by the Senate, and in all likelihood, confirmed in short order.

As I’ve mentioned several times, this is the procedure that the Democrats voted to pursue in November when they voted for the so-called “nuclear option.” The Majority voted to eliminate the filibuster on nominations, and to cut the Minority out of the process.

So, while the Senate is debating these district court nominees, it gives me a good opportunity to continue the discussion about how the Senate ought to be functioning.

There’s no debate that the Senate isn’t functioning properly, and we’ve been treated to relentless finger-pointing from the other side regarding who is to blame.

Unless we can establish a non-partisan account of how the Senate ought to function, this debate will amount to nothing more than a kindergarten shouting match.

So, I would like to return to the Federalist Papers, which are the most detailed account from the time the Constitution was being ratified about how our institutions were intended to operate.

Although they were written over 200 years ago, the principles the Federalist Papers articulate are timeless and the problems they highlight are strikingly relevant to today.

The last time I addressed the Senate on this subject, I quoted at length from a passage in Federalist Number 62.

Although all the Federalist Papers were published under the pseudonym Publius, we know that they were written by three of our Founding Fathers – James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay.

Federalist 62 has been attributed to the Father of the Constitution, James Madison.

In it, he lists several problems that can be encountered by a Republic that the U.S. Senate was specifically designed to counteract.

The first point Madison makes is that having a second chamber composed differently than the House makes it less likely that one faction will be able to take over and enact an agenda out of step with the American People.

The second point deals with the tendency of unicameral legislatures to yield to sudden popular impulses and pass “intemperate and pernicious resolutions.”

The third point is that based on the experience of the early, unicameral state legislatures, a second chamber with longer terms and a more deliberative process will make sure that any laws passed are well thought out.

The Framers of our Constitution determined that it was better to get it right the first time than to subject the American people to the upheaval caused by the need to fix poorly conceived laws.

Madison talks about the early American experience with “all the repealing, explaining, and amending laws” which he calls:

“monuments of deficient wisdom;

-so many impeachments exhibited by each succeeding against each preceding session;

-so many admonitions to the people, of the value of those aids which may be expected from a well-constituted senate.”

In my last speech, I did not get to Madison’s fourth and final point in Federalist 62, which is quite long and deserves to be examined in detail.

Madison concludes Federalist 62 with an extensive discussion of the importance of stability to good government and the danger to the rule of law from constant change.

This section starts: “Fourthly. The mutability in the public councils arising from a rapid succession of new members, however qualified they may be, points out, in the strongest manner, the necessity of some stable institution in the government.–

“Every new election in the States is found to change one half of the representatives.

“From this change of men must proceed a change of opinions; and from a change of opinions, a change of measures.

“But a continual change even of good measures is inconsistent with every rule of prudence and every prospect of success.

“The remark is verified in private life, and becomes more just, as well as more important, in national transactions.”

Here, Madison is making a case for stable government instead of constant change.

He says that constant change, even with good ideas, will not produce positive results.

Madison then elaborates on the various problems caused by an unstable government.

He first says about a country that is constantly changing its laws that “…she is held in no respect by her friends; that she is the derision of her enemies; and that she is a prey to every nation which has an interest in speculating on her fluctuating councils and embarrassed affairs.”

Madison then makes the case that the domestic ramifications of constantly enacting and changing laws “poisons the blessing of liberty itself.”

He goes on to explain, “It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood; if they be repealed or revised before they are promulgated, or undergo such incessant changes that no man, who knows what the law is to-day, can guess what it will be to-morrow.”

This sounds like the Health Care Law, which is being rewritten daily on the fly by the Obama Administration.

But, it’s part of a bigger problem we face with new laws and regulations from agencies, which have the force of law, being churned out in such a volume that no American can possibly know them all.

Just based on probability, Americans are likely to violate some regulation or another without knowing it at any time.

Madison is making a case not just for more thoughtful laws, but fewer laws.

When the Majority Leader and many in the media complain that the Senate should be passing laws at a higher rate, they miss the point entirely.

To listen to some members of the majority and many in the media, you would think the success of a session of Congress was measured solely on the sheer number of laws passed, not the quality of the laws it passes.

The Senate was specifically designed to slow down the process and make sure Congress passes fewer, but better laws.

Madison then elaborates further on why fewer laws are better in a passage that is extremely relevant today:

“Another effect of public instability is the unreasonable advantage it gives to the sagacious, the enterprising, and the moneyed few over the industrious and uniformed mass of the people. —

“Every new regulation concerning commerce or revenue, or in any way affecting the value of the different species of property, presents a new harvest to those who watch the change, and can trace its consequences; a harvest, reared not by themselves, but by the toils and cares of the great body of their fellow-citizens.”

In other words, a situation where Congress is constantly changing the laws gives more influence to those who can hire lawyers to keep on top of the changes, and lobbyists to influence them, versus the little guy who is on his own.

It is sometimes said that big businesses don’t like regulations, but that isn’t my experience in many instances.

The bigger and wealthier a business, or a union, or other special interest group, the better chance they have to shape a new law or regulation and the more people they can hire to help them comply.

On the other hand, small businesses and individuals can’t hire a team of lawyers to read the latest laws and regulations and to fill out the proper paperwork.

Small businesses and individuals are the ones squeezed out of the marketplace by the constant flow of new laws.

An overactive government benefits the big guys at the expense of the little guys, and if you think that fact is lost on the big guys and their lobbyists when they come to Congress, you would be mistaken.

As James Madison so wisely noted, an overactive government is an invitation to the rich and powerful to use government to their benefit and the detriment of their competitors.

That goes to show that there’s a great benefit to stability in law as opposed to constant change.

A cornerstone of liberty is the Rule of Law, meaning the law is transparent and no one is above the law.

If you look around the world today, the poorest and least free countries are the ones where there is no rule of law.

If someone can take what you’ve earned through force and you have no legal recourse, that’s an example where there is no rule of law.

If the rich and powerful get special privileges, that’s an example where the rule of law has broken down.

The Rule of Law is one of the principles our country was founded on.

But, when there are so many rules, and they are changing so quickly that the average citizen cannot keep up, that undermines the Rule of Law.

Of course, the situation is only made worse when the rules already on the books are waived for the politically connected.

That is another problem but one that has become all too common under the Obama administration.

Getting back to the Senate’s role, I’m not making a case for doing nothing, or that we should be happy with the failure of the Senate to debate legislation.

The Senate is supposed to be slow and deliberative, not stopped.

Still, it is important to get away from this notion that somehow the failure to ram legislation through the Senate with little debate and no amendments is the problem.

The reason the Senate doesn’t function when the majority leadership tries to run it that way is very simple:

The Senate was not designed that way.

The Senate was intended to be a deliberative body, and has been for most of its history.

It has now become routine for the Majority Leader to file cloture to end consideration of a matter immediately upon moving to it.

By contrast, the regular order is for the Senate to consider a matter for some period of time, allowing senators from all parties to weigh in, before cloture is even contemplated.

Cloture was invented to allow the Senate to end consideration of a matter after the vast majority of senators had concluded it had received sufficient consideration.

Prior to that, there was no way to end debate so long as at least one senator wished to keep deliberating.

Cloture was a compromise between the desire to move things along and the principle that each senator, as a representative of his or her state, has the right to participate fully in the legislative process.

The compromise was originally that two-thirds of senators voting had to be satisfied that a matter had received sufficient consideration.

That was reduced to three-fifths of all senators.

Each time this matter is renegotiated, the compromise leans more in favor of speeding up the process at the expense of allowing senators to fully represent the people of their states.

Now, the majority leadership routinely files cloture immediately upon proceeding to a matter.

Again, cloture is a tool to cut off further consideration of a matter when it appears that it is dragging on too long.

You can hardly claim that the Senate has taken too much time to deliberate over something when it hasn’t even begun consideration of the matter.

According to data from the Congressional Research Service, there were only seven times during the first session of the current Congress that the Senate started to consider a bill for a day or more before cloture was filed.

That’s out of 34 cloture motions related to legislative business.

The number of same-day cloture filings has more than doubled compared to when Republicans last controlled the Senate.

Moreover, the total number of cloture motions filed each session of Congress under this majority leadership has roughly doubled compared to the period from 1991 to 2006 under majority leaders of both parties.

Before that, cloture was even more rare.

This is a sign that cloture is being overused, even abused by the majority.

Still, if this alarming rise in cloture motions was a legitimate response to a minority of senators insisting on extended debate to delay proceedings beyond what’s necessary for reasonable deliberation, otherwise known as a filibuster, it might be justified.

That’s clearly not the case when the overwhelming number of motions to cut off debate are made before debate has even started.

What amount of time is necessary for deliberation, and what is purely dilatory in any particular case is a subjective determination.

However, the practice of routinely moving to cut off consideration of virtually every measure when there has not yet been any deliberation cannot be justified.

This is an abuse of the cloture motion.

Along with the routine blocking of amendments, cloture abuse is preventing senators from doing what we are paid to do — that’s represent the people of our states.

Shutting senators out of the deliberative process isn’t just an argument about dry Senate procedure, as the Majority Leader has tried to suggest in response to criticisms.

When senators are blocked from participating in the legislative process, the people they represent are disenfranchised.

When I say that people are disenfranchised when the majority leadership shuts senators out of the process, I don’t just mean the citizens of the 45 states that elected Republicans.

The citizens of states that elected Democrat senators also expect them to offer amendments and engage with their colleagues from different parties.

Shutting down consideration of a bill before it has even been considered prevents even members of the majority party from offering amendments that may be important to the people they represent.

Voters have a right to expect the people they elect to actually do the hard work of representing them, not just be a rubber stamp for their leadership’s agenda.

Senators who go along with tactics that disenfranchise their own constituents should have to answer to those who voted them into office as to why they aren’t willing to do the job they were elected to do.

That job includes not just offering amendments when appropriate, but taking tough votes that reveal to your constituents where you stand.

The majority leader has gone out of his way to shield members of his caucus from taking votes that may hurt them back home.

Senators don’t have any right to avoid tough votes.

That’s not the deliberative process James Madison envisioned.

If we are going to have good laws that can stand the test of time, the Senate must be allowed to function as it was intended.

One aspect of what’s needed to return the Senate to its proper function as a deliberative body is to end cloture abuse.

I would ask my colleagues to reflect on all of the changes to the Senate recently, including those negotiated between the two leaders a year ago in return for a promise not to use the nuclear option, as well as the subsequent use of the nuclear option 10 months later.

Those reforms, if you can call them that, have been in the direction of reducing the ability of individual senators to represent the people of their states and concentrating power with the majority leadership.

It’s time we had some reforms to get the Senate back functioning as a deliberative body like it was intended to under our Constitution.

The Senate is supposed to be a place where all voices are heard and reason can rise above partisanship.

I would urge all my colleagues to reflect on that and think about your responsibility to the people of your state.

If we do that, I’m sure we can come up with some sensible reforms to end the abuse of cloture and restore the Senate to the deliberative body the Framers of the Constitution intended it to be.

I’ll be thinking about that and I would encourage all my colleagues to do the same.