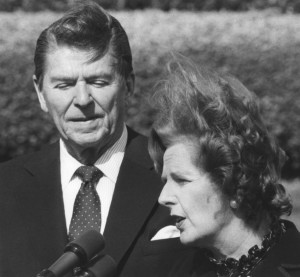

President Ronald Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher fight a stiff breeze outside the White House

WASHINGTON: President Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher fight a stiff breeze 2/26/1981 as they talk to reporters outside the White House at the conclusion of their Oval office meeting. (UPI Photo/Darryl Heikes)

LONDON, April 8 (UPI) — Margaret Thatcher, the conservative British Prime Minister known as the “Iron Lady” has died following a stroke, her spokesman said. She was 87.

“It is with great sadness that Mark and Carol Thatcher announced that their mother Baroness Thatcher died peacefully following a stroke this morning,” her spokesman said in a statement.

Thatcher was the first woman elected prime minister, a post she held from 1979 to 1990.

Prime Minister David Cameron said in a statement posted on Twitter, “It was with great sadness that l learned of Lady Thatcher’s death. We’ve lost a great leader, a great prime minister and a great Briton.”

The BBC quoted a Buckingham Palace statement as saying, “The queen was sad to hear the news of the death of Baroness Thatcher. Her Majesty will be sending a private message of sympathy to the family.”

Thatcher, born Margaret Roberts, was the first person to win a third term to the post since the 19th century and held the job longer than anyone in the 20th century.

In the national election held June 11, 1987, Thatcher’s Conservative Party scored its second-largest Parliamentary majority since World War II.

Thatcher, a grocer’s daughter who became a world figure, changed the course of British government and rekindled her country’s international prestige.

Her first eight years as prime minister, she claimed, “made Britain great again.”

She announced her resignation from office Nov. 22, 1990, while she was under fire within her own Conservative Party for her opposition to greater European Community integration on Britain’s part.

Her final term in office was plagued by several woes, including her support for an unpopular poll tax put into effect April 1, 1990 a move that sparked riots in London rising unemployment and inflation, the Persian Gulf crisis and her policy toward the EC.

Late in 1990, after falling short of the needed majority to win the Tory leadership race and under criticism from fellow Conservatives, Thatcher announced she would resign. She was succeeded as prime minister by John Major, Britain’s 47-year-old chancellor of the Exchequer.

The strong-willed Conservative Party chief led Britain to victory over Argentina in the 1982 Falklands War. And she fought for the deployment of U.S. missiles in Europe, a move that paved the way for a possible U.S.-Soviet arms reduction agreement.

On the domestic front, Thatcher governments carried out a sweeping denationalization of industry and services, curbed the power of left-wing labor unions and used prudent public spending to tame inflation.

The blond mother of two was first elected to Downing Street during the 1979 “winter of discontent,” when under a Labor Party government, unions unleashed a wave of strikes that left garbage uncollected and the dead unburied.

The self-admitted workaholic soon embarked on her policy of what she called “popular capitalism” and what others referred to as “Thatcherism.” She became a close friend of Ronald Reagan and met Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev as the most senior Western European leader.

But the social cost of the Thatcher policies has been high and her style was considered by some Britons to be domineering and uncaring. Under Thatcher, unemployment soared from 1.2 million to more than 3 million, or 11 percent of the population.

Political opponents charged her with permitting the country’s welfare state, particularly the free health and education system, to run down. Former Foreign Minister David Owen called her administration “heartless” and others claimed she stood for the privileges of the rich.

Thatcher increased public spending on the National Health Service and on schools but she also supported private medicine and private schools, saying people should have the right to choose how to spend their money.

“A vast change separates the Britain of today from the Britain of the late 1970s” her 1987 Conservative election platform boasted.

Under Thatcher, new laws curbed the unions. One of these made democratic strike votes mandatory and another outlawed secondary picketing. The number of strikes tumbled.

Under her leadership local governments sold more than 1 million low-rent public housing units to renters who became home-owners.

Her “privatization” program of such huge enterprises as the British Telecom telephone system, British Gas and British Airways put a third of formerly nationalized industries into the private sector.

Ministers said since Thatcher took office, the number of people owning stock in companies tripled to 9 million, a big step toward what she called “my great aim of making every man and woman a capitalist.”

Thatcher defended Reagan during the Iran arms scandal as “a very honest and straightforward man.

But while Reagan appeared to soften and be prepared to trade arms for the release of American hostages, Thatcher stood firm. She said she had to say “no” to families of hostages “and they may go away and think I am hard.”

Thatcher narrowly escaped an Irish terrorist bomb in 1984 that wrecked the hotel in which she was staying and killed five of her friends. She said her most important decisions as prime minister were to “stand up to people who threaten you … You must stand up to bullies and never, never give in to intimidation or violence.”

Her biggest political crisis came in 1986 when members of her Cabinet clashed over whether an American company or a European consortium should rescue Britain’s only helicopter manufacturer. Political opponents charged she was responsible for the leaking of a classified letter in the affair.

She faced a bitter struggle in an emergency debate in the House of Commons and privately admitted to doubting whether she would be able to stay on as prime minister. But in Parliament the “Iron Lady” rallied her supporters and won a vote of confidence.

Thatcher is perceived in different ways. French President Francois Mitterrand was quoted as saying she has “eyes like Caligula and the mouth of Marilyn Monroe.”

Author Anthony Burgess said that as a young woman Thatcher was attractive but had no glamour. “Glamour came with power and the need to sustain power has increased the glamour,” he said.

The lady destined to be the most famous native since Isaac Newton of Grantham, 100 miles north of London, was born Margaret Hilda Roberts above her father’s grocery store Oct. 13, 1925. Alfred Roberts, of working class origins and a devout Methodist, kept a religious house with grace recited before and after meals and no newspapers on Sunday.

“I was brought up in an atmosphere that you worked hard to get on,” Thatcher once said. “Although we didn’t have all mod cons [modern conveniences the house had no hot water upstairs and the toilet was outside in the yard], it was bright as a new pin. We were brought up in a very religious background. Caring for others ran very strongly so there was a tremendous amount of voluntary work.”

Roberts recognized early that he had an exceptional daughter. She won her first scholarship at the age of 10 and was top of her class every year but one. She did not underestimate herself. When she won first prize for poetry recitation at a drama festival her schoolmistress said:

“You were lucky, Margaret.”

“I wasn’t lucky, ” came the reply. “I deserved it.”

Thatcher’s father paid for elocution lessons to eradicate the Lincolnshire burr from her speech. A scholarship took her to Oxford a rare distinction for a girl from a small provincial school where she became only the second woman president of the University Conservative Association. She sang in the Bach Choir, studied chemistry and after graduation got a job as a research chemist at British Xylonite, working on a new bonding agent for metal and plastic.

In 1949 she impressed the chairman of the Conservative Party in Dartford in Kent and became their parliamentary candidate. At 24 she was the youngest woman in the campaign. She lost but she pushed up the Tory share of the vote. Another member of Deptford party was Denis Thatcher, whose family owned a paint factory. One night he offered her a lift home. They were married five weeks before the 1951 election in which she again increased her share of the vote without winning.

“Was it love at first sight?, she was once asked.

“No,” she said. “There were two elections to fight first.”

She moved to a research job in the laboratory of a food combine and studied patent and tax law in her spare time. She was called to the bar as a barrister four months after she gave birth to twins in 1953. Denis Thatcher, who sold his company to Burmah Oil for $1 million and was a director of the oil company until his retirement, said they had decided to try to have two children, a boy and a girl.

“Typical of Margaret,” he said, “she produced the twins, Mark and Carol, and avoided the necessity of a second pregnancy.”

After the birth of her children, Thatcher looked for a safe seat and was adopted by the upper middle-class district of Finchley in London. She was elected in 1959 and her maiden speech, in support of her own bill requiring local councils to admit the press to their sessions, brought her to the attention of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan.

In 1969 Macmillan appointed her joint parliamentary secretary at the Ministry of Pensions and she was on her way to 10 Downing Street, a goal she once admitted she began thinking about when she was 14. When the Tories were out of power 1964-70, she worked on land, transport, power and economics. In 1966 she scored a spectacular success in the opposition reply to the Labor budget. It was said she read every budget and finance speech for 20 years in preparation.

When the Tories returned to power in 1970, Prime Minister Edward Heath named Thatcher education secretary and, although she fought against it in the Cabinet, she had to supervise one of the most unpopular measures in years, cutting off free milk to schoolchildren. Children chanted “Thatcher, Thatcher, milk snatcher,” and on one occasion she wept.

There were demonstrations against her that verged on riots when she proposed more university control over student unions.

Thatcher was admired for the way she stood up to critics. “Ted Heath in drag,” sneered Labor’s rough Denis Healey. Meanwhile, there was discussion in the Conservative Party about the future of Heath. When he lost his third election to the Labor Party in 1974, Thatcher challenged him for the party leadership.

She was elected in 1975. Heath never forgave her.

Until she became prime minister, Thatcher arose at 6:30 a.m. to make her husband’s breakfast and straighten the house. She needed only 4 or 5 hours sleep a night.

“I had to sacrifice my home life ever since I entered Parliament,” she said.

She was exceptionally pretty as a girl. Her husband is credited with persuading her to tint her dark hair corn yellow, a better combination with her piercing blue eyes. She once modeled tweed suits for a newspaper layout. She was always well dressed; her mother was a dressmaker.

“I love expensive clothes,” she once said, “so I always go to the sales.”

She collected porcelain, liked opera and the theater, watched tennis and golf on TV, read detective thrillers for relaxation, drank Cointreau or scotch and soda at the end of a hard day’s work, and rated Dover sole her favorite food.

She claimed she never read anything written about her.

She was quotable.

Asked about women’s place in public life she once said: “In politics if you want anything said, ask a man. If you want anything done, ask a woman.”

On another occasion: “No one would have remembered the Good Samaritan if he’d only had good intentions. He had money as well.”

Copyright 2013 United Press International, Inc. (UPI).

I sure wish a leader like her would stand up here in the U.S.A.

She hated socialism in any form. She stood for making the people more self-reliant through capitalism. Yet when the need arose, she made it clear that Brits could rely upon those in government to protect them as happened during the Falklands.

Her comment to Bush “not to get wobbly” is perfectly characteristic of her leadership. The U.S., indeed the world lost a great friend.