By Cynthia Dizikes, Chicago Tribune –

By Cynthia Dizikes, Chicago Tribune –

CHICAGO _ Standing on the Lake Michigan shore, Jackie Kovacs saw her granddaughter fighting to swim back to land Sunday afternoon and immediately dove into the water to help.

Before she could reach the girl, Kovacs became trapped, too, in a torrent of water rushing away from Michigan’s Peterson Beach.

“It just sweeps you back,” Kovacs said this week. “It’s like something evil reaches out of the lake and wants to take you.”

A family friend and another beachgoer managed to pull Kovacs, 61, and her granddaughter from the lake. But at least two people drowned in other rip currents that surged through Lake Michigan Sunday after a violent weekend storm.

A third suspected rip-current fatality, which is still being investigated by the National Weather Service, occurred at Peterson Beach hours after Kovacs and her granddaughter were rescued.

Clusters of rip-current-related deaths have become an unfortunate norm over the years in Lake Michigan, which far outpaces the other Great Lakes in such incidents. And, since the National Weather Service began tracking fatalities and rescues in 2002, August has emerged as a particularly deadly month, according to Keith Cooley, a National Weather Service meteorologist, who specializes in Great Lakes rip currents.

“We think this is largely due to stronger storm systems _ higher winds and waves _ moving in as we get closer to fall along with an increase in people visiting the beach before summer break is over,” he said.

Another strong storm blowing toward Chicago on Thursday produced more rip-current warnings that were expected to last through Saturday. The city of Evanston closed its beaches.

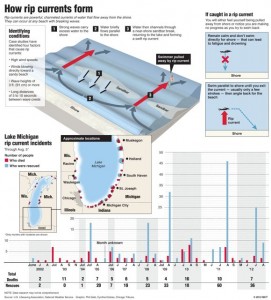

Long associated with oceans, rip currents occur in the Great Lakes when heavy winds create waves that pile water onto the shore. On its way back toward the lake, that water can then cut channels through sandbars, creating a fast-paced stream that may pull unsuspecting swimmers into deep water.

“It’s like filling a bucket with water and punching a little hole through it,” said John Fletemeyer, a coastal studies professor at Florida International University, who recently co-authored a book on rip currents. “The velocity or the pressure (of the water coming out) would be significantly increased.”

Rip currents can move 1 to 8 feet per second, according to the United States Lifesaving Association.

Although they can be hazardous to swimmers off the beaches of Chicago and the North Shore, they are more common along the shoreline of Indiana and southwest Michigan where a mix of wind, waves and sandbars can turn picturesque vistas into death traps. The Weather Service has identified the region as one of the most dangerous areas for rip currents in the Great Lakes.

“Sunday, here, is referred to as ‘SARday,’ which stands for ‘Search and Rescue,'” said Lt. Martin Kurtz, who has headed the Berrien County Sheriff’s Department’s marine division since 2007. “If we have beautiful skies, warm water and rips, we’re most likely going to be busy.”

The two confirmed rip current deaths Sunday happened at beaches in Berrien County, Mich.

Donald Liu, who was a Chicago pediatric surgeon, drowned after trying to save two children caught in a rip current off Cherry Beach. Soon after, at Tiscornia Beach, a 41-year-old man was swimming with his wife when they were both snared by a rip current. Although his wife made it back to shore, the man drowned, according to the U.S. Coast Guard.

The Weather Service began issuing rip current warnings in 2008. The U.S. Lifesaving Association estimates that more than 100 people die every year from rip currents.

Part of the problem is that rip currents can seem like relatively calm streams of water between the waves, Fletemeyer said.

If viewed from above, a rip current can sometimes look like a mushroom _ a narrow stem running from the shore and eventually diffusing beyond the breaking waves. From the shore, a rip current may appear smoother than surrounding water and murkier from churning sand and other debris. But many times, rip currents may be hard to distinguish.

In the Great Lakes, they can be about 20 to 30 feet wide and up to 150 feet long, Cooley said.

If a swimmer gets in a rip current, the Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project recommends that the person roll on their back and float to determine which way the current is moving. Then, the person should swim perpendicular to the current and back toward shore.

Experts believe more rip current incidents may happen in Lake Michigan because the relatively warm lake tends to draw more swimmers. The lake also has a long stretch of water that northerly winds can run across, causing larger waves at the southern end.

Safety measures at beaches around Lake Michigan are not uniform. Some have lifeguards. Some post flags warning about rip currents. But others may simply put up signs informing beachgoers that they are entering the water at their own risk.

Swimmers should check conditions with local authorities or the Weather Service and always swim near a lifeguard, according to experts.

Kovacs said the only warning she encountered Sunday on her way to Peterson Beach, which does not use a flag system, was related to ticks. If she had known there were potential rip currents in the area, Kovacs said she never would have gone to the beach with her granddaughter. Kovacs said she believes that all designated beaches around Lake Michigan should be required to post rip current warnings.

“It’s really disturbing,” Kovacs said. “When we got there, there were great, big blue skies and billowy clouds. It just looked like a normal, wavy beach.”